Every year during the great migration about 1.3 million wildebeest, together with 200,000 zebra and half a million Thomson’s gazelle, move around the ecosystem – over 2 million animals in all.

They all converge on the plains in the wet season because that is where the best food is. The grasses of the plains have the highest protein content in the whole of Serengeti, but they are also high in calcium and phosphorus.

The animals move around the plains following the rainstorms and the growth pattern of grasses.

The three migrant grazers, however, stick to themselves with only a small overlap in their distributions, taking advantage of the different heights of grass.

How do they migrate?

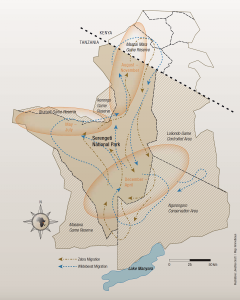

The long journey of the wildebeest and zebra is a continual trip in the search for fresh food. There is neither a starting point nor a finish line. There are only a few intermissions on the long way between areas with abundant rainfall in the North and the nutrient-rich pastures in the South where they stay a bit longer before continuing the rounds again.

As the plains turn green with the first rain, usually around December, the Thomson’s gazelle arrive first, feeding on the short new growth. Then as the grass grows a little taller the wildebeest arrive and displace the gazelle which now move further east to the short grass plains. Eventually, the zebra arrive and they confine themselves largely to the intermediate grass plains. They all move back west in reverse order when the plains dry out in May.

June sees the migration moving west and north. They move slowly – both because it takes time to graze long grass and because they are wary of predators. Wildebeest dictate the movements of the other species. They eat down the grass and provide a niche for the gazelle that follow behind. Zebra like to stay with wildebeest because they are safer there, but they must stay in front because they need a greater bulk of food than the wildebeest.

Once the herds reach the woodlands this pattern breaks up and smaller groups of wildebeest and zebra make their way west and north. Thomson’s gazelle stay behind in the central woodlands. The beginning of the rains in November brings the migrants south and east again towards the edge of the plains. They only congregate again when the rains become more consistent and the herds move onto the plains.

The text is an excerpt from “Serengeti Story” by Dr Anthony Sinclair (with kind permission of the author). Sinclair is a Professor Emeritus of Ecology at University of British Columbia, Canada.